Landon Carter Haynes

The first child of David and Rhoda Haynes, Landon Carter Haynes was born on December 2, 1816, in Carter County, Tennessee. A farmer and slave owner, he was also an attorney, newspaper editor, and briefly, a Methodist minister. However, Landon Carter Haynes is best remembered as a legislator, politician, and Confederate senator from Tennessee.

In 1837, the heirs of John Tipton, Jr. sold the 200-acre farm to David for $1,050. In 1839, Landon married Eleanor Powell of Elizabethton, Tennessee and as a wedding gift from David and Rhoda, the newlyweds were given the former Tipton home and property. Before moving into the home, he attended Washington College and was one of five students who graduated in 1838. Following graduation, he studied law with Thomas A. R. Nelson and was admitted to the bar in 1840.

In 1841, Haynes became editor of the Tennessee Sentinel, a newspaper published by his brother-in-law, Lawson Gifford. The Sentinel was published in Jonesborough, Tennessee and was a “strongly Democratic” newspaper, which created a political feud between Haynes and William G. Brownlow and his Jonesborough Whig newspaper. The feud escalated when Haynes and Brownlow began fighting in the streets of Jonesborough. As Brownlow beat Haynes over the head with a pistol, Haynes produced a pistol of his own and shot Brownlow through the thigh. This ended the scuffle, but not their bitter rivalry. Haynes went on editing the Sentinel until Lawson Gifford sold the paper in 1846.

Landon Cater Haynes entered the political arena in 1844 as the Democratic candidate for presidential elector in the First Congressional District of Tennessee. During that election year, he campaigned for Democrat James K. Polk, the Democratic presidential candidate from Tennessee. An 1844 flyer from Wytheville, Virginia lists “Colonel L. C. Haynes” as a democratic speaker for a political “Grand Mass Meeting” of the presidential election.(1) Polk won the 1844 presidential election by defeating Whig candidate Henry Clay and became the 11th president.

In 1845, Haynes decided to run for a seat in the Tennessee state legislature. He was elected to the lower house, where he represented Washington, Greene, and Hawkins Counties during the 26th General Assembly (1845-1847). During this assembly, Haynes voted for the creation of a deaf and dumb school in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Haynes opted out of running against fellow Democrat Andrew Johnson for Congress in 1847, but instead sought election to the upper house of the Tennessee state legislature. He was elected to the 27th General Assembly (1847-1849) and represented the counties of Carter, Johnson, Sullivan, and Washington. During this assembly, Haynes introduced a bill to incorporate the East Tennessee and Virginia Railroad Company. The bill passed on the first reading and the company was to construct a railroad from Knoxville to Bristol, Tennessee, which would then connect with a southern Virginia terminus being constructed from Lynchburg, Virginia.

During the 1848 presidential election, Haynes again campaigned as a Democratic presidential elector. The presidential candidate whom Haynes campaigned for was Democrat Lewis Cass of Michigan. Cass defeated Free Soil candidate Martin Van Buren, but was runner-up to Whig candidate Zachary Taylor, who became the 12th president.

From 1849 through 1851, Haynes served in the 28th General Assembly in the lower house of the Tennessee state legislature. He represented the counties of Washington, Greene, and Hawkins. During this assembly, Haynes was elected speaker of the state house of representatives. This marked the high point of his career as a state legislator.

In 1851, Haynes opposed Democrat Andrew Johnson for the election to the United States House of Representatives – the Whig party did not nominate any candidate to oppose the two Democrats. In the toughest campaign of his political career, a contemporary described the campaign as “intensely bitter and personal.” (2) Johnson defeated Haynes by more than 1,600 votes.

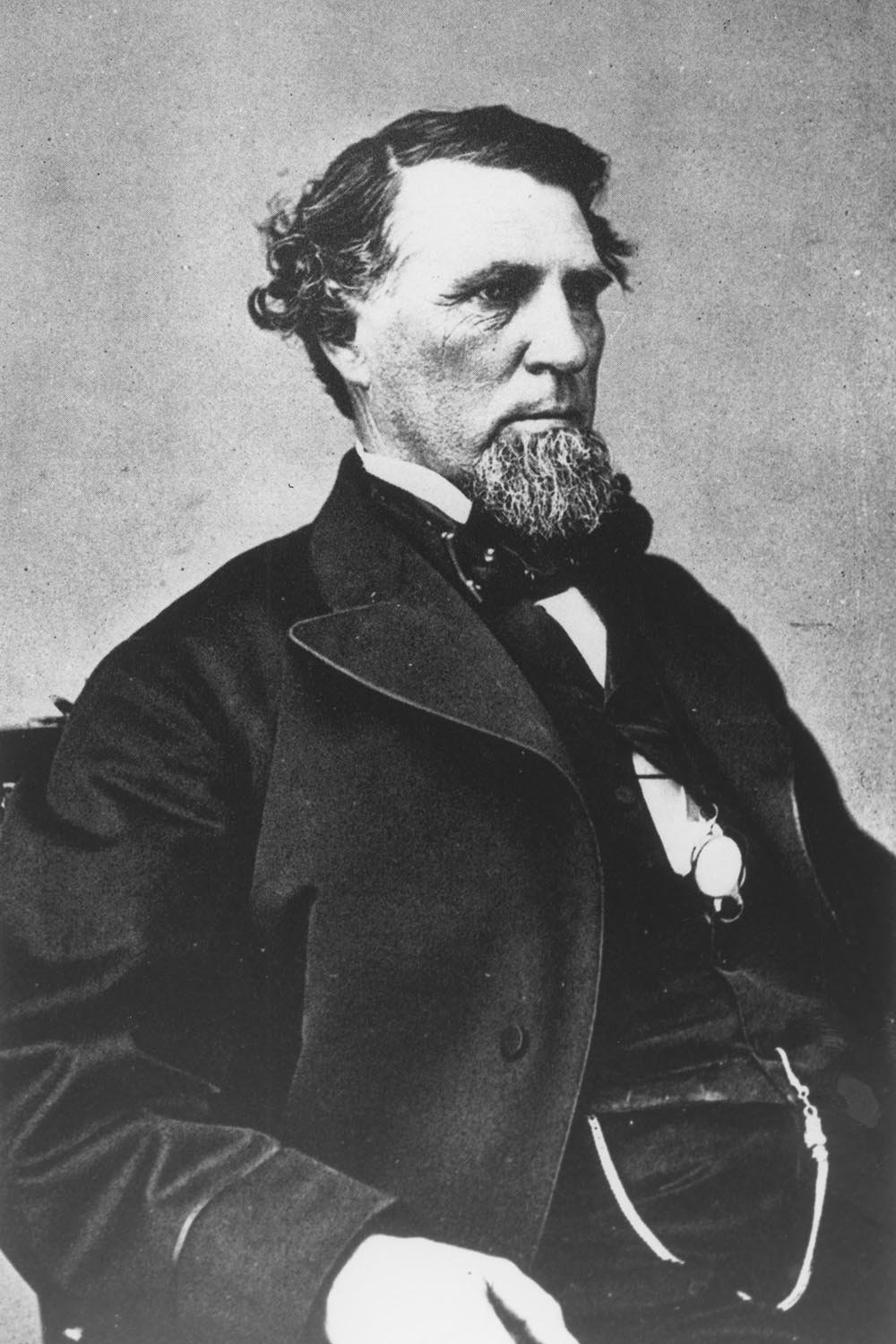

After this defeat, Haynes focused primarily on his law practice, but after nearly a decade out of politics, Haynes again ran for Congress in 1859. This time his opponent was his former law instructor, Thomas A. R. Nelson. In contrast to the earlier contest between Haynes and Johnson, “politeness and courtesy characterized this otherwise strenuous struggle.” (3) In this campaign, Haynes barely lost to his Whig opponent by ninety votes.

Even though he had been defeated in his Congressional bid, Haynes still had something to celebrate that year. In 1859, the United States government changed the Johnson’s Depot post office name to Haynesville in honor of him. As the Civil War began, the United States changed the name back to Johnson’s Depot, but the Confederate States of America still referred to the place as Haynesville.

During the controversial 1860 presidential election, Haynes campaigned for John C. Breckenridge as the (Southern) Democratic presidential elector. In his campaigning, he traveled throughout East Tennessee, and in a possible attempt to expand his political outreach, he purchased a lot in Knoxville, Tennessee. With the election of Abraham Lincoln and the beginning of secession talk, Haynes strongly advocated Tennessee’s secession. Even before Tennessee and many other Southern states seceded, Haynes delivered a pro-secession speech in Knoxville in January, 1861. In his speech, he asserted that Tennessee should “…feel that her union with the Southern States…is natural and inseparable, and the unalterable condition of her present and future safety, prosperity, and independence” is bound to the South. (4) To the pleasure of Haynes, Tennessee seceded later that year.

His support and openness of Tennessee’s secession led to his unanimous election to represent Tennessee in the Confederate States of America Congress from 1862 to 1865. During the First and Second Congressional sessions, Haynes participated on several committees: Judiciary, Patents, Post Offices and Post Roads, Printing, Commerce and Engrossment and Enrollment (which he chaired in the First Congress).

Recent research of the Confederate Conscription Act of 1862 reveals that Haynes contributed more to this act than what was previously known. The Confederate Conscription Act of 1862 was the first ever draft enforced in America. Even with this act, certain people of the Confederacy were exempt from being drafted. The “Twenty Slave Clause” allowed at least one male (owner or overseer) to be exempt from the draft if he owned or was to oversee twenty or more slaves. Haynes voted against the “twenty slave” amendment when Congress passed an exemption bill in the fall of 1862. Also, he proposed and voted on another part of the exemption bill that pertained to the members of local militia. Being passed along with the “twenty slave” amendment, Haynes’ militia amendment stated that local militia members were exempt from the draft provided that it was necessary for the militia members to be present to repel possible invasions from the enemy. (5)

While not attending Congress in the Confederate capitol of Richmond, Virginia, Haynes lived with his family in Knoxville. When not worrying about the issues of Congress, Haynes also fretted about his two oldest sons. By mid-1862 Robert and Joseph Haynes had both enlisted in the Confederate army. Being officers, limited battle action was seen by both during the war. However, both were mainly stationed in East Tennessee, Southwest Virginia, and Western North Carolina. Robert was also a part of Confederate General Braxton Bragg’s Kentucky Campaign of 1862.

As the war progressed in 1863, Knoxville was threatened by a Federal raid in June. With a limited number of Confederate troops defending the town, local citizens participated in the defense. Confederate Lieutenant Colonel Milton A. Haynes in his report of the raid states, “Among many citizens who reported to me that day for duty, I must not forget to mention Hon. Landon C. Haynes….” (6) With such bravery, Haynes and the Confederate defenders thwarted the Federal raiders from Knoxville and their homes.

Although Knoxville was saved for the moment, a few months later in September of 1863, Knoxville fell to a Federal army under the command of General Ambrose Burnside. With the fall of Knoxville, Haynes relocated with his family to Wytheville, Virginia. Disgusted with how little attention was given in maintaining Confederate control of East Tennessee by the government, Haynes attributed and charged Confederate President Jefferson Davis with the fall of Knoxville and of his home state of Tennessee. Not only was his home state under Federal authority, but his farm in Haynesville was as well.

By early 1865, the Confederacy’s existence was becoming all but lost. As Petersburg, Virginia fell to Federal hands, the Confederate government in Richmond decided to evacuate in early April 1865. Congress was in session at this time, so Haynes and his family joined the refugee government in their flight to North Carolina – the last remaining state in Confederate control. With Confederate armies surrendering throughout the South, the war also came to an end for Haynes in Statesville, North Carolina. He was arrested and told to stay in town until paroled or pardoned by the United States government.

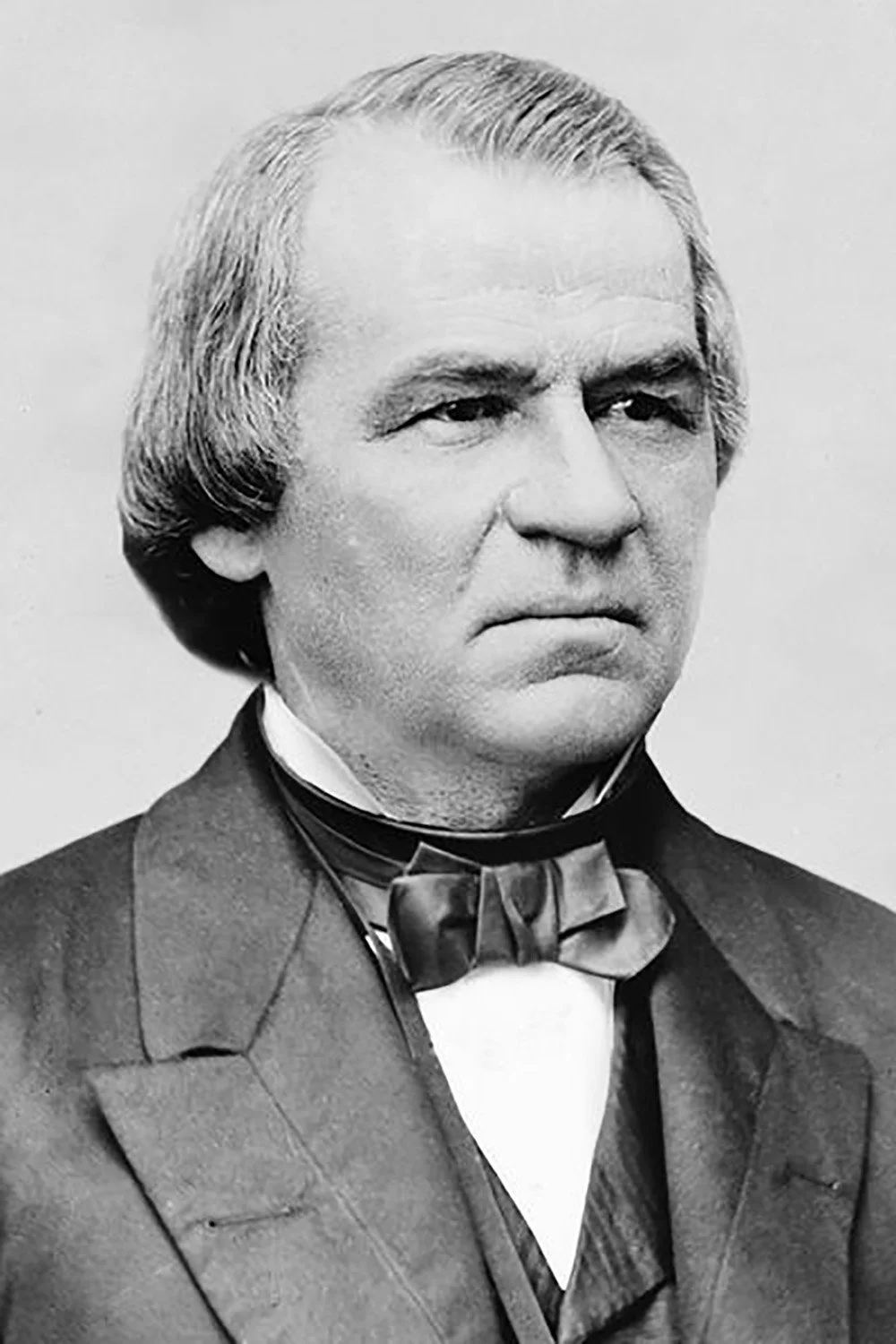

With the conclusion of the war, President Andrew Johnson issued his amnesty proclamation on May 29, 1865. This proclamation was extended to former Confederates seeking parole and pardon for their participation during the rebellion. When granted amnesty by the United States government, all rights protected by the Constitution would be fully restored back to each individual, except the right of owning former slaves. Not long after, Haynes applied for pardon. On August 20, 1865, Haynes traveled to nearby Salisbury, North Carolina and took the oath of allegiance to the United States. Also on that same day, Haynes wrote a letter to former rival President Johnson requesting a personal interview with the President and inquired if he would allow him to travel to Washington, D. C. for the interview. It is not known if President Johnson replied to Haynes’ request or if the personal interview ever took place.

Not only did Haynes apply himself in obtaining a pardon, but he also had three of North Carolina’s top officials writing on his behalf to President Johnson. In a letter dated August 9, 1865 William W. Holden, North Carolina’s Provisional Governor at the time, wrote the president:

Sir: You know Mr. Haynes better than I do. He has been leading a very quiet life at Statesville, in this State. Chief Justice Pearson [Richmond M. Pearson, serving in the state’s Supreme Court at the time] and Judge Fowle, [Daniel G. Fowle, serving as the judge of the state’s superior court] whose letters are enclosed, recommend that he be pardoned. (7)

After taking the oath of allegiance in August, Haynes was paroled but not officially pardoned. As he remained in North Carolina, his farm back in East Tennessee was auctioned off by the Federal government. With his farm gone and fearing possible retribution from Unionists in East Tennessee, Haynes decided in February of 1866 to relocate with his family to Memphis, Tennessee. This almost proved to be a dreadful decision.

With Haynes not officially pardoned and now residing in Tennessee, newly elected Governor William Brownlow (Republican), former political and personal rival and staunch East Tennessee Unionist, had the Federal Court in Knoxville indict Haynes for treason in the spring of 1866 for his participation with the secession movement in Tennessee. The stunned Haynes wrote President Andrew Johnson on June 6, 1866 appealing for him to step in on his behalf since the government had still not accepted his pardon petition in almost a year, which made possible his indictment by Governor Brownlow. Five days later, Haynes was officially pardoned by President Johnson on June 11, 1866 and the treason charge was dropped.

Being formally pardoned, the Civil War was officially over for Landon Carter Haynes. He was able to settle comfortably in Memphis with his family to start anew during Reconstruction. Immediately he pursued his passion – practicing law. He joined three other men in town and they established the Office of Haynes, Heath, Lewis & Lee, Attorneys at Law.

In 1872, Landon Carter Haynes attended a banquet in Jackson, Tennessee in honor of the bench and bar during a session of the Supreme Court. Another dignitary at the banquet was former Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest, who harbored no affection for Unionist East Tennessee. Well aware that Haynes was a native of that region, Forrest delivered the following toast to the former Confederate senator: “Mr. Chairman, I propose the health of the eloquent gentleman from East Tennessee, sometimes called the God-forsaken country.” In response to the toast from General Forrest, Haynes delivered a short speech now known as the “Ode to Tennessee.”

Mr. Chairman and Gentlemen: I plead guilty to the soft impeachment. I am from East Tennessee. Evidently the distinguished soldier proposing that toast was not himself born breathing the pure air of the mountains. At least I understand he was reared in the sluggish atmosphere of a lagoon far back in the swamps of Mississippi.

Yes, I was born in East Tennessee – on the banks of the Watauga which in the Indian vernacular means beautiful river. And beautiful river it is! Standing upon its banks in my childhood, I have looked down through its glassy waters and beheld a heaven below and then looking up beheld a heaven above, reflecting like two great mirrors each into the other its moon and planets and trembling stars! Away from its banks of rock and cliff, cedar, hemlock and laurel, stretches a vale back to the distant mountains, more beautiful than any in Italy or Switzerland. There stand the great Unaka, the great Roan, the great Black and the great Smoky Mountains, among the loftiest in America, on whose summits the clouds gather of their own accord even on the brightest day. There I have seen the great Spirit of the Storm after noon-tide go take his evening nap in his pavilion of darkness and of clouds. Then I have seen him aroused at midnight like a giant refreshed by slumber, covering the heavens with gloom and greater darkness, as he awoke the tempest and let loose the red lightings that ran along the mountain tops for a thousand miles swifter than an eagle’s flight in heaven! And now the lightening would stand up and dance like angels of light in the clouds to the music of that grand organ of nature whose keys seemed touched by the fingers of Divinity in the hall of eternity, sounding and resounding in notes of thunder through the universe!

Then I have seen the darkness drift away, and the morn getting up from her saffron bed, like a queen put on her robes of light, come forth from her palace in the sun and tiptoe on the misty mountain top, whilst night fled before her glorious face to his bed chamber at the pole, as she lighted the beautiful river and the green vale where I was born and played in childhood with a smile of sunshine.

O beautiful land of the mountains with thy sun-painted cliffs how can I ever forget thee! (8)

The same year, the Democratic Party in Memphis selected Haynes as their candidate for Congress. Haynes’ opponent was Republican Barbour Lewis. Throughout the campaign Haynes attacked Lewis’ ability as a political leader, as an honest man, and the Republican Party. At one point during the campaign, Haynes slandered Lewis by calling him a “carpetbagger” – a name given to Northerners and Republicans seeking political and financial benefit from the war-torn South during the Reconstruction. (9) In the end, his reputation of being a former secessionist and Confederate senator led to his defeat.

Haynes retired from politics after his defeat and again focused on practicing law. On February 17, 1875, Landon Carter Haynes succumbed to congestion of the brain (or a stroke) and died in his Memphis home. His death was lamented by many and the Memphis bench and bar adopted two resolutions in his honor:

Resolved; That in the death of Landon C. Haynes, the Bar has been deprived of one of its most gifted members; that society has lost a most noble gentlemen, and that the community has lost one of its most distinguished citizens.

Resolved; That the members of this Bar tender to his bereaved and stricken family their heart felt condolence, in this hour of their deep affliction. (10)

Haynes was buried in Memphis, but years after his death, his son Robert reinterred him in Jackson, Tennessee where he lived and practiced law as his father did. With this reinternment, the great East Tennessee Orator rested in an unmarked grave until several Tennessee Sons of the Confederate chapters placed a monument atop the possible location of his resting place.

Samuel Shaver portrait of David Haynes.

Samuel Shaver portrait of Rhoda (Taylor) Haynes.

Samuel Shaver portrait of Eleanor (Powell) Haynes.

Headline of a March 27, 1840 edition of the Tennessee Sentinel, one year before Haynes became one of the paper's editors.

Civil War era photograph of William Brownlow courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Civil War era photograph of Andrew Johnson courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Civil War Era photograph of T. A. R. Nelson courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Confederate capitol in Richmond, Virginia courtesy of Natural Concepts.

Photograph of Landon Carter Haynes taken by famed Civil War photographer Mathew Brady after the war. Courtesy of the National Archives & Records Administration.

Letterhead of the Memphis attorney office of Haynes and his partners.

Photograph of Landon and Eleanor Haynes taken after the Civil War while they were living in Memphis.

-

(1) Haynes, Landon Carter: broadside (1844), Tipton-Haynes Historic Site Civil War Exhibit Collection, Tipton-Haynes State Historic Site, Johnson City, Tennessee.

(2) Oliver P. Temple, Notable Men of Tennessee from 1833 to 1875: Their Times and Their Contemporaries (New York: The Cosmopolitan Press, 1912), 378.

(3) Haynes, Landon Carter: from Alexander, Thomas B., Thomas A. R. Nelson of East Tennessee (1956), Tipton-Haynes Historic Site Civil War Exhibit Collection, Tipton-Haynes State Historic Site, Johnson City, Tennessee.

(4) Philip M. Hamer, Tennessee: A History, 1673-1932 (New York: The American Historical Society, Inc., 1933), 1: 531.

(5) Confederate Senate, Journal of the Congress of the Confederate States of America, 1861-1865 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904), 2: 294-297 & 311-312.

(6) Haynes, Landon Carter: from The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records, Tipton-Haynes Historic Site Civil War Exhibit Collection, Tipton-Haynes State Historic Site, Johnson City, Tennessee.

(7) Haynes, Landon Carter: presidential pardon file (1865-66), Tipton-Haynes Historic Site Civil War Exhibit Collection, Tipton-Haynes State Historic Site, Johnson City, Tennessee.

(8) Haynes, Landon Carter: Emory & Henry College Archives, Tipton-Haynes Historic Site Civil War Exhibit Collection, Tipton-Haynes State Historic Site, Johnson City, Tennessee.

(9) Haynes, Landon Carter: from Fraser, Walter J. Jr., “Barbour Lewis: A Carpetbagger Reconsidered” (1973), Tipton-Haynes Historic Site Civil War Exhibit Collection, Tipton-Haynes State Historic Site, Johnson City, Tennessee.

(10) Haynes, Landon Carter: Memphis (Tenn.) documents, Tipton-Haynes Historic Site Civil War Collection, Tipton-Haynes State Historic Site, Johnson City, Tennessee.

-

Confederate Senate. Journal of the Congress of the Confederate States of America, 1861-1865. Vol. 2. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904.

Haynes Family Collection. Tipton-Haynes State Historic Site, Johnson City, Tennessee.

Mary Hardin McCown Collection. Tipton-Haynes State Historic Site, Johnson City, Tennessee.

Temple, Oliver P. Notable Men of Tennessee from 1833 to 1875: Their Times and Their Contemporaries. New York: The Cosmopolitan Press, 1912.

Tipton-Haynes Historic Site Civil War Exhibit Collection. Tipton-Haynes State Historic Site, Johnson City, Tennessee.

-

Figure 1. Samuel Shaver portrait of David Haynes.

Figure 2. Samuel Shaver portrait of Rhoda (Taylor) Haynes.

Figure 3. Samuel Shaver portrait of Eleanor (Powell) Haynes.

Figure 4. The headline of a March 27, 1840 edition of the Tennessee Sentinel, one year before Haynes became one of the paper's editors.

Figure 5. Civil War era photograph of William Brownlow. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Figure 6. Civil War era photograph of Andrew Johnson. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Figure 7. A Civil War Era photograph of T. A. R. Nelson. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Figure 8. A photograph of the Confederate capitol in Richmond, Virginia. Courtesy of Natural Concepts.

Figure 9. This photograph of Landon Carter Haynes was taken by famed Civil War photographer Mathew Brady after the war. Courtesy of the National Archives & Records Administration.

Figure 10. A letterhead of the Memphis attorney office of Haynes and his partners.

Figure 11. This photograph of Landon and Eleanor Haynes was taken sometime after the Civil War while they were living in Memphis.