Colonel John Tipton

Born in Maryland on August 15, 1730, Colonel Tipton moved to Frederick County in northern Virginia, where he married Mary Butler around 1750. When the Colonial Virginia Assembly created Dunmore County in 1772, Colonel Tipton was one of the first justices of the peace in the new county.

Serving as a captain for the Virginia militia, Colonel John Tipton was a veteran of Lord Dunmore’s War (1774). The War was a campaign waged by the colony of Virginia against the Shawnee Indians and resulted in the westward expansion of Virginia’s boundaries. Although he served as a captain for the Virginia militia, he is more commonly known as colonel for when he served that position for the North Carolina militia in the late 1780s.

Also in 1774, on June 16, Colonel Tipton served as a member of the committee that drafted the Dunmore County (or Woodstock) Resolutions that protested the harsh treatment allotted to Boston, Massachusetts after the Boston Tea Party. The signed document is viewed as a precursor to the Bill of Rights and contains revolutionary rhetoric that was developing throughout the British colonies. Early the next year, Colonel Tipton was elected to the Dunmore County committee of safety and correspondence.

Colonel Tipton also served in the American forces during the Revolutionary War (1776 – 1783). Although he spent most of his time in the realm of politics, Colonel Tipton aided the war effort by serving as a recruiting officer for the Virginia militia. In 1776, he represented Dunmore County at the Fifth Virginia Convention in Williamsburg. The convention declared Virginia independent from Great Britain and drafted a state constitution with a Declaration of Rights. Founding Fathers Thomas Jefferson and James Madison along with Patriot Patrick Henry served alongside Tipton during this convention. From 1776 to 1781, he was a member of the Virginia General Assembly, representing Dunmore County and its successor, Shenandoah County. For the remainder of the war, he served as sheriff of Shenandoah County from 1781 to 1783.

Tipton suffered two painful losses during the war. While giving birth to their ninth son, Jonathan, Mary Butler died on June 8, 1776. Just over a year later Colonel Tipton married Martha Denton Moore, a recent widow, on July 22, 1777. The other loss came in 1782 when his son Abraham was killed while fighting British backed Native American forces near the Falls of the Ohio River.

In 1783, the Treaty of Paris ended the long war between Great Britain and the thirteen American colonies, now formally recognized as the United States of America. That same year, Colonel Tipton moved with his family from Virginia to present-day Tennessee, which at that time was the western part of North Carolina. The next year he purchased a few tracts of land in Washington County, including a 100-acre tract on Catbird Branch of Sinking Creek from Samuel Henry. Accompanying Colonel Tipton on the move to Tennessee was his second wife, some of the younger Tipton children from his first marriage, and Abraham, who was born in 1780 and the only son of Colonel Tipton and Martha. He also brought slaves from Virginia to Washington County, but unfortunately there is no document that gives an accurate account of how many slaves accompanied him. According to Washington County, Tennessee Tax Records, Colonel Tipton listed five blacks along with two stud horses in 1797.

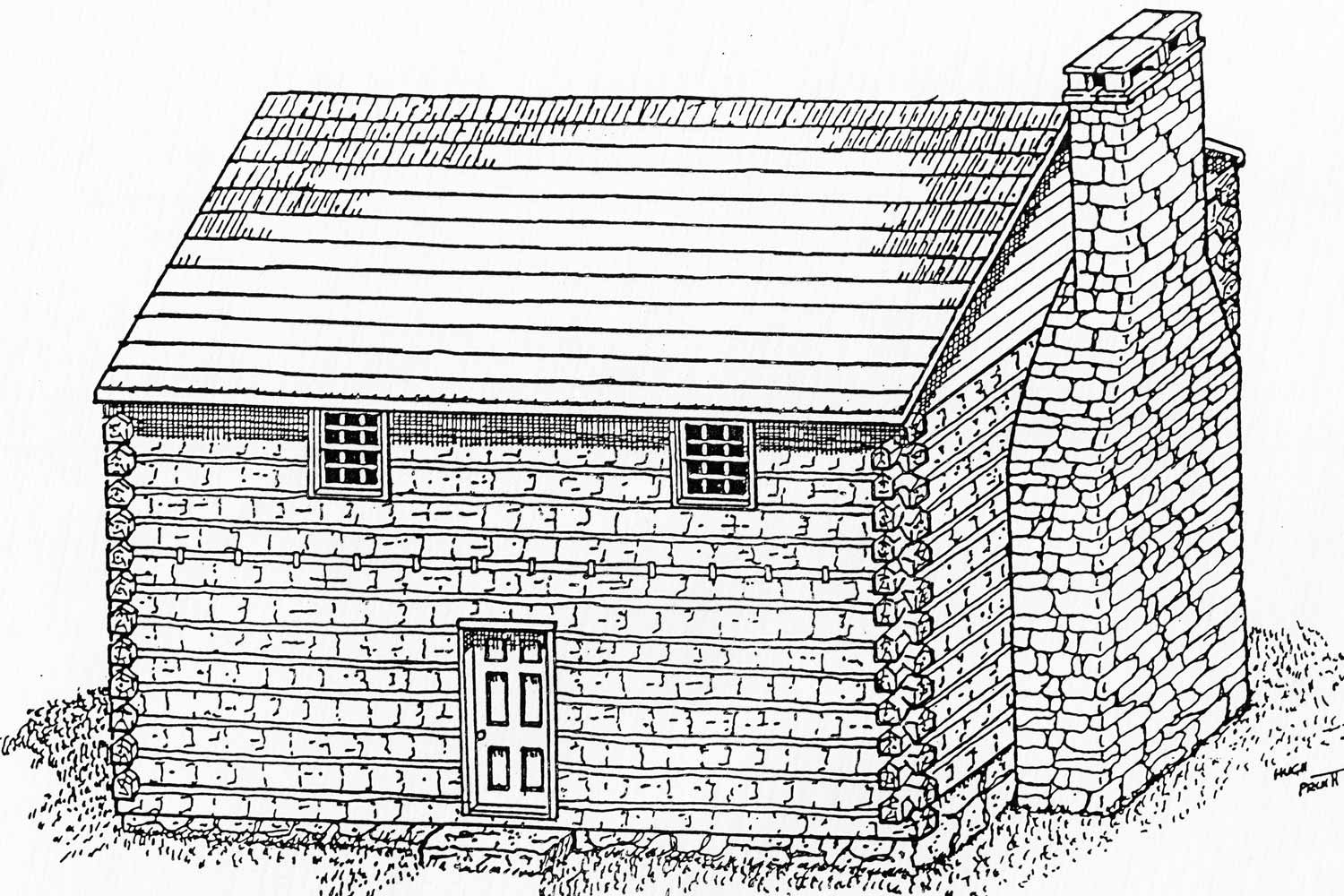

When the Tiptons moved to the region, the residents of what is now northeast Tennessee lived in three counties: Washington County, created in 1777 as the first county in present-day Tennessee; Sullivan County, created from Washington County in 1779; and Greene County, carved from Washington County in 1783. Colonel Tipton’s home was located ten miles from Jonesborough, which had been established in 1779 as the county seat of Washington County and the first town in present-day Tennessee. In a letter to nineteenth century historian Lyman C. Draper, Thomas Love described the Tipton cabin as “a large size house, some 25 by 30 feet, hewn logs – a story and a half – no windows below – two or 3 window holes, round, in each gable and above – a door in front.” (1)

The scene of tranquility was not found by the Tiptons as the controversial State of Franklin was formed on August 24, 1784. The area of present-day Northeast Tennessee was plunged into a political and personal unrest for four years as North Carolina and the State of Franklin struggled to determine governmental rule for the area. Colonel Tipton was quickly swept into the political turmoil as he was selected to represent Washington County in the State of Franklin First Constitutional Convention on December 14, 1784, and Second Constitutional Convention on November 14, 1785. He voted against the Franklin Constitution both times. In August of 1786, he was elected to represent Washington County in the North Carolina Senate. A few months later he was appointed colonel of the North Carolina militia for Washington County.

Growing tensions came to a climax in February of 1788. Early that month, the North Carolina sheriff of Washington County, Jonathan Pugh, was ordered by the county court under Colonel Tipton to seize property of John Sevier, the Franklin governor, for his owed taxes to the state. Sheriff Pugh obeyed the orders and seized some of Sevier’s property, including several slaves, from his home while he was absent in Greene County. Sevier’s property and slaves were brought to Colonel Tipton’s cabin for safekeeping by Sheriff Pugh. This action led to the Battle of the State of Franklin.

Governor Sevier was furious when the news of Pugh’s seizure reached him days later. His anger was based upon his feud with Colonel Tipton, and that Pugh’s actions violated the Franklin Act that was passed in March of 1787. This legislation stated that any person attempting to perform any official act under North Carolina authority was subject to punishment. Sevier decided to march upon Colonel Tipton’s cabin and raised a small force of loyal Franklinites in Greeneville (the state’s capitol).

Hearing of Governor Sevier’s actions, Colonel Tipton wrote his militia subordinate, Major Robert Love. He directed him to gather his Greasy Cove (present-day Unicoi County, Tennessee) men and march to his house quickly. Fearing the worst, Colonel Tipton told Major Love, “Let no time be lost.” (2)

On February 27, 1788, Governor Sevier and his force, numbering over 100 men, arrived at Colonel Tipton’s cabin. They positioned themselves a few hundred yards from his house and set pickets up along the property. Colonel Tipton was now surrounded in his cabin with only his family and a handful of supporters.

Governor Sevier sent a flag of truce to Colonel Tipton on February 27, and requested that he and his party “surrender themselves to the discretion of the people of Franklin within thirty minutes from the arrival of the flag of truce.” (3) In a letter to Joseph Martin dated March 21, 1788, Colonel Tipton wrote about receiving Sevier’s flag: “To this daring insult I sent no answer.” (4) While Tipton refused Sevier’s offer, the first attempt of assistance for Colonel Tipton was done by a company from Washington County under the command of Captain Peter Parkinson. Before reaching the cabin, Captain Parkinson’s company was fired upon by the Franklinites near the spring and still houses of Colonel Tipton. In a letter written on March 10, 1788, Colonel Tipton and Colonel George Maxwell state that three horses were the only causalities as a result of this skirmish. (5) In a sworn deposition of August 20, 1788, Colonel Tipton and others stated that Sevier’s sentinels “took five of his [Capt. Parkinson’s] men prisoner and killed a horse….” (6)

With tensions heightened on both sides, a unique incident occurred shortly after the firing ceased between Captain Parkinson’s company and Sevier’s sentinels. Described best in Colonel Tipton’s deposition, “Two young women passing by near to the still house before mentioned were fired upon from which firing one of them received a bullet through her shoulder.” (7) The women that were fired upon were not named and, unfortunately, there is no source that documents whether the wound was fatal or not.

The next day, February 28, Governor Sevier sent another flag of truce to Colonel Tipton requesting his surrender. Colonel Tipton replied boldly this time, “To this flag I sent an answer, letting the men assembled there know that all I wanted was a submission to the laws of North Carolina, and if they would acquiesce with this proposal I would disband my troops here….” (8) Realizing that Colonel Tipton and his small party were not going to surrender, Sevier decided to lay siege to Tipton’s cabin instead of causing any bloodshed by assaulting the cabin.

After sneaking out of Tipton’s cabin on the night of the 27th, Major Robert Love had joined with his brother, Thomas Love, in raising a small party to reinforce Colonel Tipton. On the evening of the 28th, Major Love’s party had reached the outskirts of the Tipton property. Fearing possible detection from Franklinite sentries, Major Love volunteered to check for a possible path around. He soon found that the Franklinite sentries had left their post around the cave due to the bitter cold weather. Major Love quickly went back and told his force that the path was clear, and they safely dashed to the cabin.

Colonel Tipton and his men’s spirits were again lifted on February 29. Colonel George Maxwell and his North Carolina loyalists from Sullivan County reached the Tipton cabin early that morning. This detachment, equivalent to Sevier’s force, arrived during a heavy snowstorm and was not detected by Sevier’s men. Not knowing exactly who fired first, both sides fired a volley at each other and upon hearing the shots, Colonel Tipton decided to attack Sevier. While dashing out of his cabin, Colonel Tipton exclaimed, “Boys, every man who is a soldier come out.” (9)

The fight was brief, but conclusive. After roughly ten minutes of fighting, Governor Sevier and his men retreated back to Jonesborough, while several men were captured and wounded on both sides. The causality rate of the battle was low and is best explained by a loyalist, Dr. Taylor, who stated that neither side wished to kill each other. Instead, some men were poorly or not even armed and did not even load their guns. According to Dr. Taylor, Colonel Tipton’s men shot in the air while Sevier’s men shot at the corners of the cabin. (10) Three men were killed, though, as a result of the battle, two being North Carolina loyalists and one Franklinite. Sheriff Jonathan Pugh was mortally wounded in the chest and died several days after the fighting.

Colonel John Tipton and his men pursued after the fleeing Franklinites. In their pursuit, the loyalists were met by Robert Young, Jr., who delivered a verbal message from Governor John Sevier to Colonel Tipton and his officers. Sevier asked Tipton for time to consider terms and Colonel Tipton replied by allowing him until March 11 to submit to the laws of North Carolina. Governor Sevier and the Franklinites held a council to consider their options and on March 3, Sevier sent the council’s results to Colonel Tipton – Sevier’s term as governor had expired two days earlier and therefore, he signed the document as only the president of the council. The Franklin council wished for peace but did not comply with Colonel Tipton’s request to submit to the laws of North Carolina. As the State of Franklin’s existence began to diminish, tension still prevailed between the Franklinites and Tiptonites.

During the summer of 1788, delegates of North Carolina meet to consider ratifying the newly written Constitution of the United States. Colonel Tipton was one of five delegates from Washington County to attend this meeting. During the convention, a draft of a bill of rights and a list of amendments to the Constitution were debated. In the end, the convention neither rejected nor ratified the Constitution. Colonel Tipton and all but two delegates from the state’s western territory (present-day Tennessee), along with one hundred and eighty-one other delegates voted against ratifying the Constitution until a list of rights were added to it, while only eighty-three delegates voted in favor of ratification.

In December of 1789, the North Carolina legislature ceded the state’s western territory (present-day Tennessee) to the new federal government for the second time. Congress accepted the cession bill, and in May of 1790, Congress created the Territory South of the River Ohio or commonly known as the Southwest Territory. The next month, President George Washington appointed William Blount of North Carolina as governor of the new territory.

In October of 1793, Governor Blount called for the election of a territorial house of representatives. Colonel John Tipton and Leroy Taylor represented Washington County. Meeting in Knoxville in 1794 and 1795, the territorial assembly chose a delegate to represent the territory in the U.S. Congress, created a system of taxation, provided for the administration of justice in the territory, and established a treasury department. The assembly also established colleges, created new counties, and chartered new towns throughout the territory. In June of 1795, the assembly directed that a territorial census be held in the fall, along with a poll of all free males (age eighteen and older) on the question of statehood for the territory. The census revealed that more than seventy-five thousand people resided in the territory, and a large majority of those who voted in the poll favored statehood for the territory.

Consequently, Governor Blount authorized the election of five delegates from each county in the territory, who met in January of 1796 to form a government for the proposed new state. Colonel Tipton and four other men represented Washington County in the January constitutional convention. That month, Colonel Tipton and his fellow delegates assembled in Knoxville “for the purpose of forming a Constitution, or form of Government, for the permanent government of the people….” (11) Colonel Tipton was appointed to a committee given the responsibility of drafting a constitution and bill of rights for the prospective state.

The constitution drafted in Knoxville was later described by Thomas Jefferson as “the least imperfect and most republican” of the state constitutions. (12) Modeled in large part after the constitutions of North Carolina and Pennsylvania, the state’s first constitution provided for a bicameral legislature, a popularly-elected governor, and a system of courts to be created by the legislature.

The Constitution of 1796 gave voting rights to all free adult males (including free blacks) who were at least twenty-one years old. The bill of rights guaranteed freedom of speech, religion, press, peaceable assembly, trial by jury, and security against unjustifiable search and seizure. The name of the proposed state would be Tennessee. The delegates chose not to submit the constitution to popular referendum, but a copy of the document was hastily sent to the U.S. Congress in Philadelphia.

The first session of the Tennessee legislature met at Knoxville in March of 1796. During this session, Colonel Tipton represented Washington County in the state senate. The primary accomplishment of this first legislature was implementing the new state government. The legislators certified the election of the ever-popular John Sevier as the state’s first governor, elected two United States senators, and created four new counties.

In the meantime, President George Washington submitted the state constitution to Congress. At this time the House of Representatives was controlled by the Republican Party (Democratic-Republicans) who favored statehood for Tennessee. The Senate was dominated by Federalists who opposed the possible statehood of Tennessee. After much debate in the Senate, the House and Senate created a joint committee to consider the statehood question. The committee approved statehood, both houses of Congress accepted the committee report, and Tennessee became the 16th state of the Union on June 1, 1796.

By the early 1800s, Colonel Tipton retired from public life and returned to his log home in Washington County. In 1813, he died and was buried on a small hill on his land. The cemetery is now the resting place of the Tipton, Gifford, and Simerly families.

Artist Hugh Pruitt's interpretation of Colonel Tipton's cabin c. 1784.

Portrait of John Sevier courtesy of Natural Concepts.

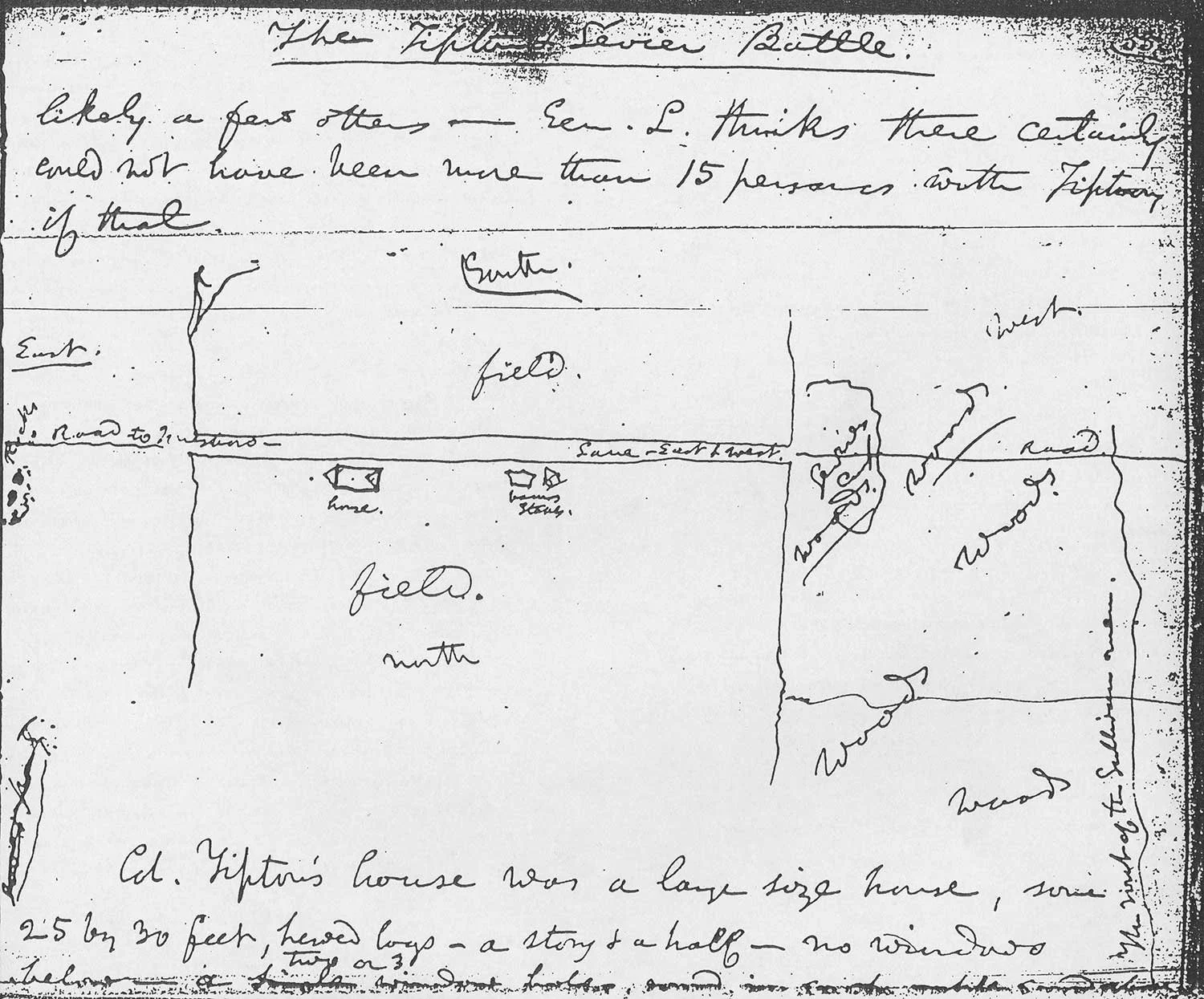

Map drawn by nineteenth century historian Lyman C. Draper of Tipton property during the Battle of the State of Franklin.

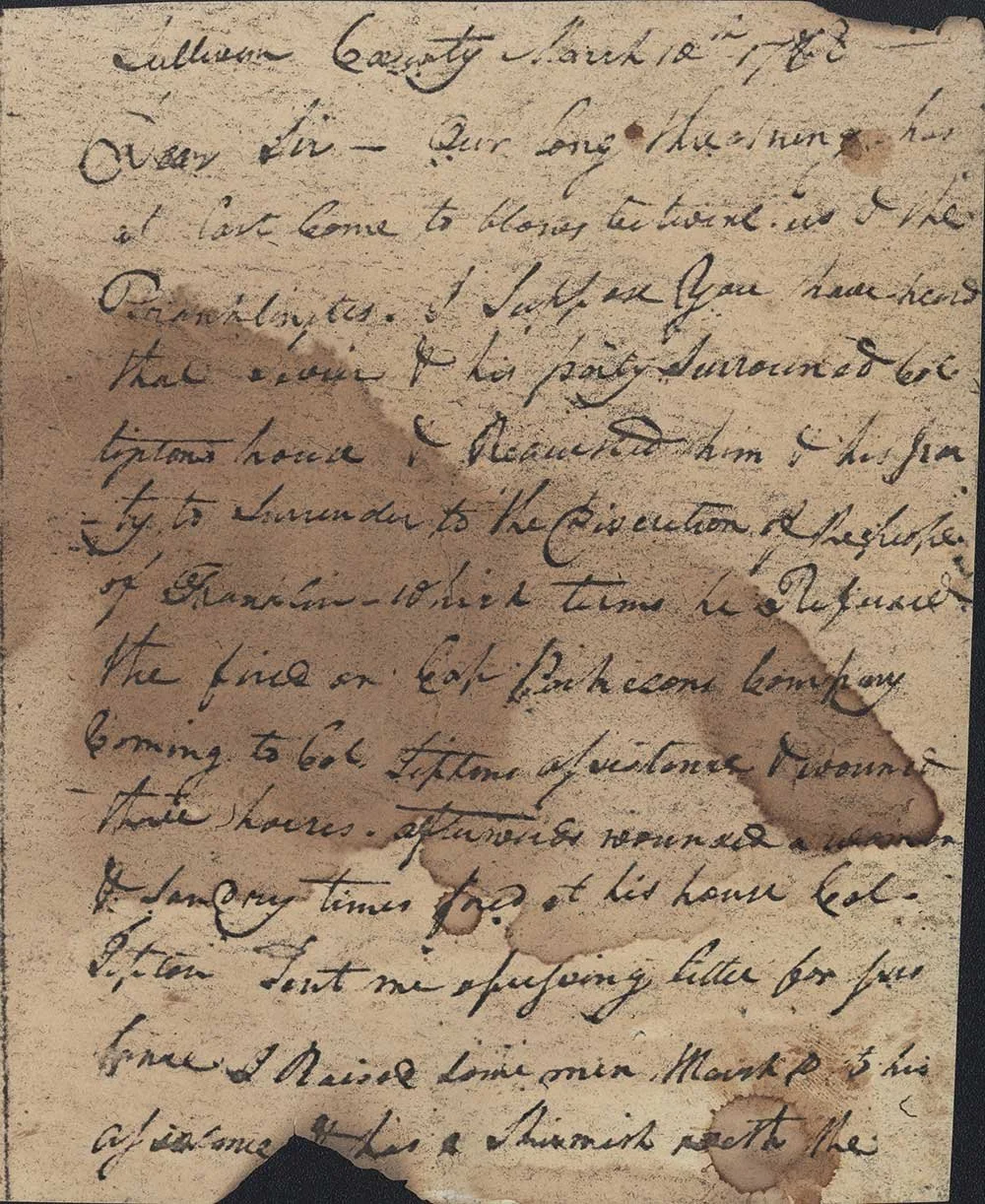

Letter from Colonel Tipton and Colonel Maxwell to Colonel Arthur Campbell.

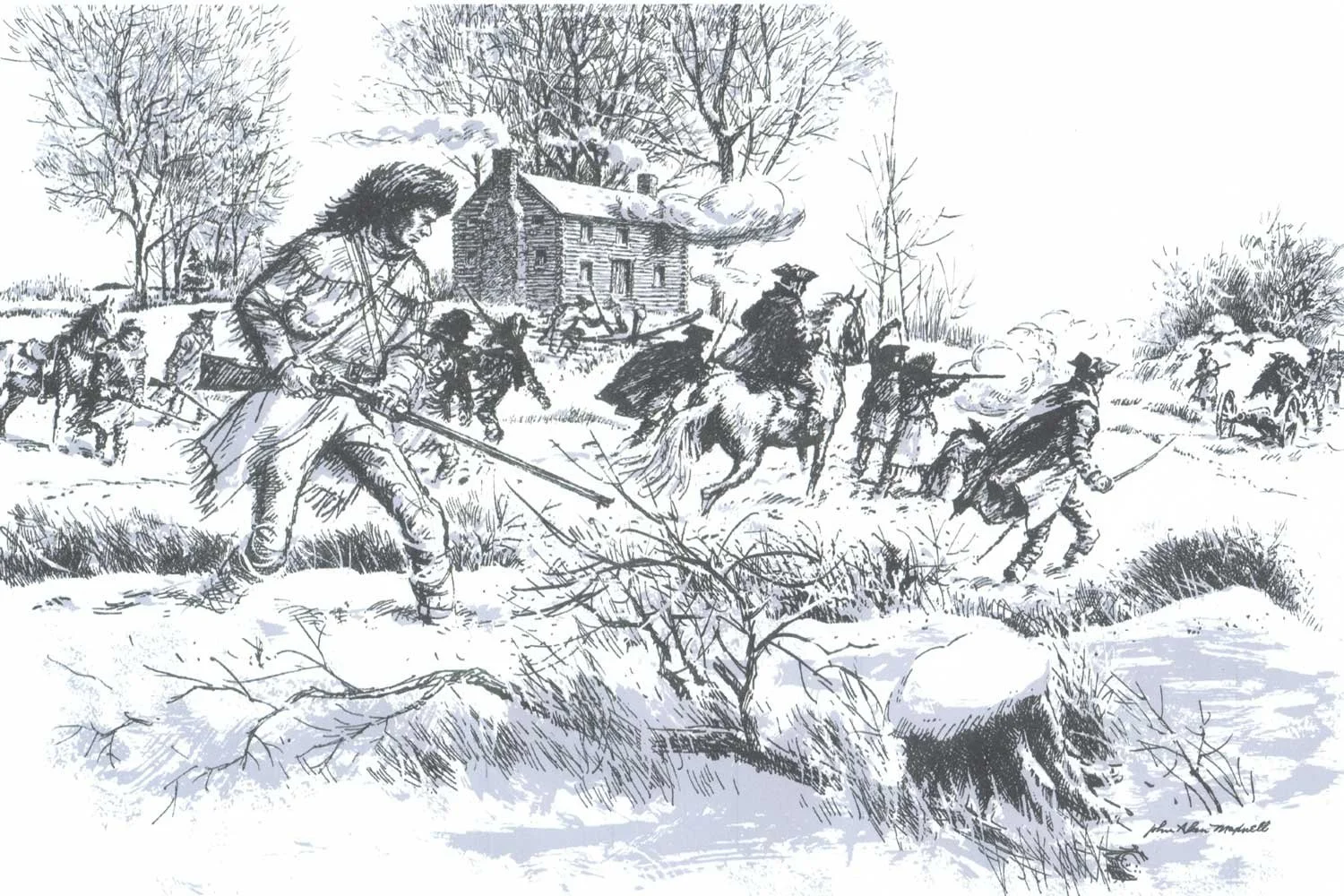

John Alan Maxwell’s depiction of the Battle of the State of Franklin, February 29, 1788.

Portrait of William Blount courtesy of Natural Concepts.

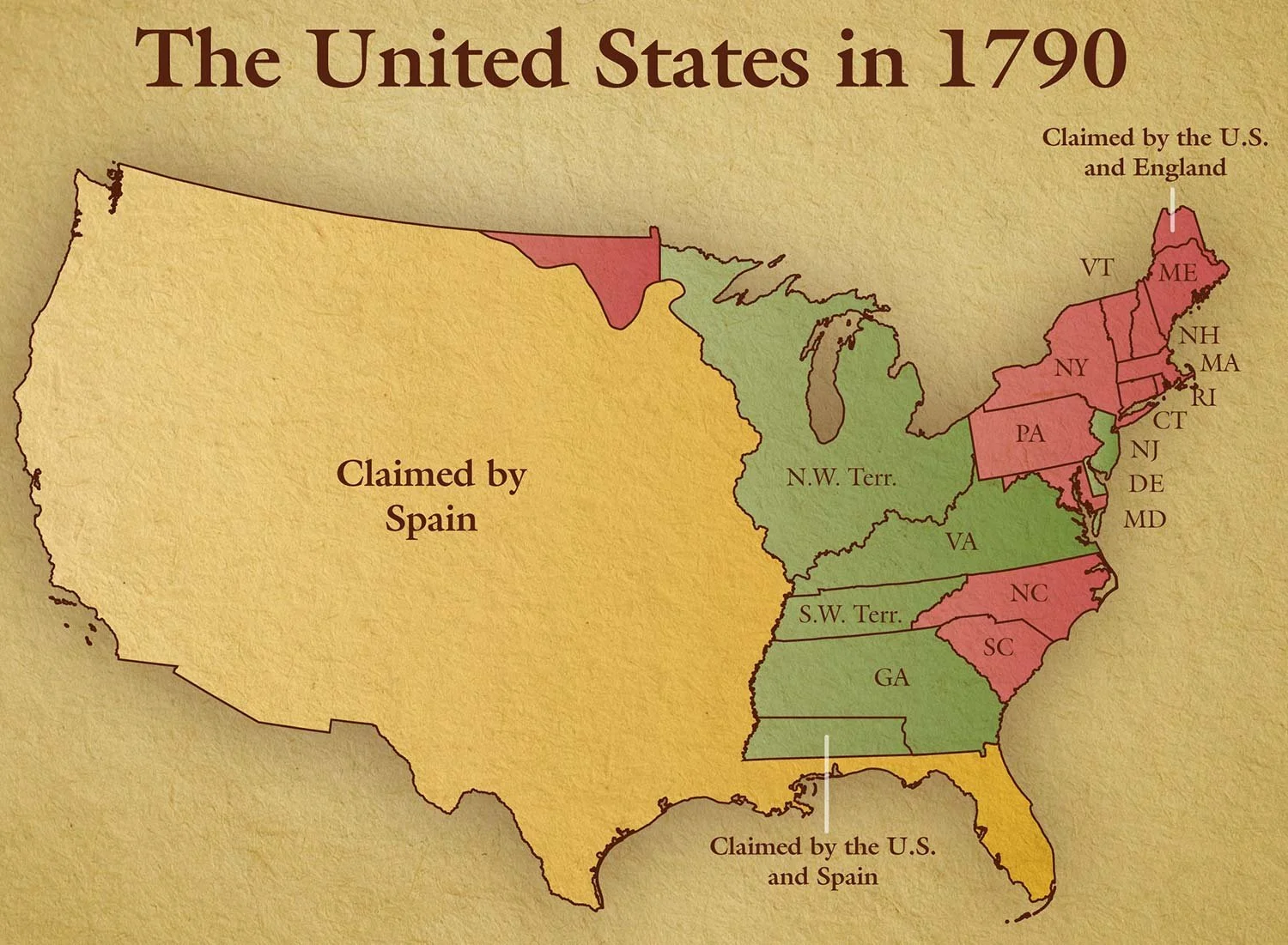

Map of the United States in 1790 showing the Southwest Territory courtesy of Natural Concepts.

-

(1) Draper Manuscripts, Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison, Wisconsin.

(2) J. G. M. Ramsey, The Annals of Tennessee, (1853; repr., Kingsport, Tennessee: Kingsport Press, Inc., 1967), 414.

(3) Clark, The State Records of North Carolina, 22: 714.

(4) Ibid, 692.

(5) John Tipton & George Maxwell to Col. Arthur Campbell, March 10, 1788, Mary Hardin McCown Collection.

(6) Deposition of Colonel John Tipton & others, Mary Hardin McCown Collection.

(7) Ibid.

(8) Clark, The State Records of North Carolina, 22: 692.

(9) Draper Manuscripts, Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison, Wisconsin.

(10) Ramsey, The Annals of Tennessee, 412.

(11) Edward T. Sanford, “The Constitutional Convention of 1796,” in Proceedings of the Annual Session of the Bar Association of Tennessee (Nashville, Tennessee: Marshall & Bruce Co., Printers and Stationers, 1896), 97.

(12) Ramsey, The Annals of Tennessee, 657.

-

Abernethy, Thomas Perkins. From Frontier to Plantation in Tennessee: A Study in Frontier Democracy. 1932. Reprint, Tuscaloosa, University of Alabama, 1967.

Alderman, Pat. The Overmountain Men. 1970. Johnson City, Tennessee: The Overmountain Press, 1986.

Clark, Walter, ed. The State Records of North Carolina. 20 vols. Goldsboro, North Carolina: Nash Brothers, 1895-1911.

Corlew, Robert E. Tennessee: A Short History. 2nd ed. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1981.

Draper, Lyman Copeland. The Tipton-Sevier Battle. Draper Manuscripts. Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison, Wisconsin.

Abernethy, Thomas Perkins. From Frontier to Plantation in Tennessee: A Study in Frontier Democracy. 1932. Reprint, Tuscaloosa, University of Alabama, 1967.

Alderman, Pat. The Overmountain Men. 1970. Johnson City, Tennessee: The Overmountain Press, 1986.

Clark, Walter, ed. The State Records of North Carolina. 20 vols. Goldsboro, North Carolina: Nash Brothers, 1895-1911.

Corlew, Robert E. Tennessee: A Short History. 2nd ed. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1981.

Draper, Lyman Copeland. The Tipton-Sevier Battle. Draper Manuscripts. Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison, Wisconsin.

Finger, John R. Tennessee Frontiers: Three Regions in Transition. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001.

Indiana Historical Bureau. “Northwest Ordinance of 1787. http://www.in.gov/history/2695.htm (accessed August 2010).

Library of Congress. “Documents from the Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convention, 1774-1789.” http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/bdsdcc:@field (DOCID+@lit(bdsdcc13401)) (accessed August 2010).

“Northwest Ordinance.” http://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/ northwest.html (accessed August 2010).

Mary Hardin McCown Collection. Tipton-Haynes State Historic Site, Johnson City, Tennessee.

Our Documents. “Northwest Ordinance (1787).” http://ourdocuments.gov/doc.php? flash=true&doc=8 (accessed August 2010).

Ramsey, J. G. M. The Annals of Tennessee. 1853. Reprint, Kingsport, Tennessee: Kingsport Press, Inc., 1967.

Sanford, Edward T. “The Constitutional Convention of 1796.” In Proceedings of the Annual Session of the Bar Association of Tennessee, 92-135. Nashville, Tennessee: Marshall & Bruce Co., Printers and Stationers, 1896.

Speer, Ed. “Constitutions.” In The Tennessee Handbook, 45-83. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2002.

Tennessee Constitutional Convention. Journal of the Convention of the State of Tennessee: Convened for the Purpose of Revising and Amending the Constitution Thereof. Nashville, Tennessee: W. H. Hunt and co., printers, 1834.

Tipton Family Collection. Tipton-Haynes State Historic Site, Johnson City, Tennessee.

William G. Cooper Collection. Tipton-Haynes State Historic Site, Johnson City, Tennessee.

Williams, Samuel Cole. History of the Lost State of Franklin. Rev. ed. 1933. Reprint, Johnson City, Tennessee: The Overmountain Press, 1993. Finger, John R. Tennessee Frontiers: Three Regions in Transition. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001.

Indiana Historical Bureau. “Northwest Ordinance of 1787.” http://www.in.gov/history/2695.htm (accessed August 2010).

Library of Congress. “Documents from the Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convention, 1774-1789.” http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/bdsdcc:@field (DOCID+@lit(bdsdcc13401)) (accessed August 2010).

“Northwest Ordinance.” http://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/ northwest.html (accessed August 2010).

Mary Hardin McCown Collection. Tipton-Haynes State Historic Site, Johnson City, Tennessee.

Our Documents. “Northwest Ordinance (1787).” http://ourdocuments.gov/doc.php? flash=true&doc=8 (accessed August 2010).

Ramsey, J. G. M. The Annals of Tennessee. 1853. Reprint, Kingsport, Tennessee: Kingsport Press, Inc., 1967.

Sanford, Edward T. “The Constitutional Convention of 1796.” In Proceedings of the Annual Session of the Bar Association of Tennessee, 92-135. Nashville, Tennessee: Marshall & Bruce Co., Printers and Stationers, 1896.

Speer, Ed. “Constitutions.” In The Tennessee Handbook, 45-83. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2002.

Tennessee Constitutional Convention. Journal of the Convention of the State of Tennessee: Convened for the Purpose of Revising and Amending the Constitution Thereof. Nashville, Tennessee: W. H. Hunt and co., printers, 1834.

Tipton Family Collection. Tipton-Haynes State Historic Site, Johnson City, Tennessee.

William G. Cooper Collection. Tipton-Haynes State Historic Site, Johnson City, Tennessee.

Williams, Samuel Cole. History of the Lost State of Franklin. Rev. ed. 1933. Reprint, Johnson City, Tennessee: The Overmountain Press, 1993. -

Figure 1. Artist Hugh Pruitt's interpretation of how Colonel Tipton's cabin appeared in 1784.

Figure 2. John Sevier. Courtesy of Natural Concepts.

Figure 3. Map drawn by nineteenth century historian Lyman C. Draper of Col. Tipton's property during the Battle of the State of Franklin. This map was drawn from the memory of Thomas Love, younger brother of Robert Love, during an interview by Draper. Col. Tipton's house is visibly marked, along with Gov. Sevier’s position in the woods.

Figure 4. Page 1 of 2 of a letter from Col. Tipton and Col. Maxwell to Col. Arthur Campbell. The letter, dated March 10th, explains the recent conflict between the Tiptonites and Franklinites.

Figure 5. John Alan Maxwell’s depiction of the February 29, 1788 Battle of the State of Franklin. Maxwell, 1904 – 1984, was a native of Johnson City, Tennessee and a prominent mid-twentieth century artist. John’s brother, Clifford Maxwell, was a charter member of the Tipton-Haynes Historical Association and a well-known photographer.

Figure 6. Image of William Blount. Courtesy of Natural Concepts.

Figure 7. United States map of 1790 showing the Southwest Territory. Courtesy of Natural Concepts.